Why Am I Suddenly Struggling to Run? Understanding Your Threat Bucket

Feb 12, 2026If you’ve been asking yourself, why am I suddenly struggling to run?—even though your training hasn’t dramatically changed—you’re not alone. When pace feels harder, recovery stalls, or nagging symptoms flare up out of nowhere, it’s easy to assume you’re overtraining or doing something wrong. But your body doesn’t separate running stress from life stress, and when your total load exceeds your capacity, things can start to unravel. To understand why you’re suddenly struggling to run, you have to look beyond mileage and consider the full picture of stress, recovery, and resilience.

Ask yourself: how are you feeling? This post by Jenna Kutcher really hit the nail on the head for this collective “mad at the world” feeling I have right now.

This matters, even when we talk about running and fitness, because we are whole humans. Our bodies are affected by far more than workouts and mileage. It isn’t always great at sorting stress into neat categories. It doesn’t always reliably distinguish between training stress, emotional stress, social stress, or existential dread. This means that sometimes you can be getting feedback from your body (fatigue, pain, poor recovery) that has very little to do with your training plan and everything to do with the rest of your life, or even the state of the world around you.

When the Metrics Start to Slide

A former client reached out to me recently. She’s an experienced athlete who has taken what she learned in the Women’s Running Academy and, after working one-on-one with me, built her own training program. She’s been executing it well and was about two weeks out from a big race.

Suddenly, things felt like they were crashing, and there was that nagging question: why am I suddenly struggling to run? Her heart rate variability and other metrics were trending down and, more importantly, she felt it in her body and sent me a panicked message.

My first response was reassurance: she was two weeks out, she had done the work, and she didn’t need to add anything right now. Then (knowing her) I asked a different set of questions. How was her nervous system? Had she been doing any nervous system regulation practices we worked on? What else was happening in her life? What occurred in the days leading up to the drop in her metrics?

When she reflected, she could identify one particularly hard workout layered on top of two major life stressors. I encouraged her to revisit a nervous system regulation technique from the Women’s Running Academy. After doing it, she felt clearer and could suddenly see how all the pieces connected. Her metrics began to climb again.

Her body wasn’t failing. It was struggling to filter multiple forms of stress and recovery stalled as a result. In these cases, sometimes training needs to be adjusted and other times the key is recognizing and addressing the non-training stressors.

Why Am I Suddenly Struggling to Run? Stress, Adaptation, and Capacity

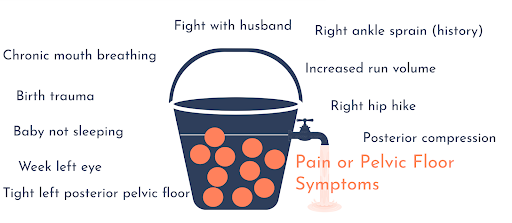

This brings us to the idea of the threat bucket (credit goes to Missy Bunch for this one). Pain and other symptoms are multifactorial. If you view every ache, injury, or setback solely through a biomechanical lens or as a volume problem, you may miss essential pieces and repeatedly set yourself up for frustration.

That doesn’t mean biomechanics don’t matter. Volume is still a major variable we can manipulate. Sometimes it really is as simple as doing too much, too soon. AND sometimes when you’re doing “all the right things” it can feel like one plus one no longer equals two.

That’s often when people start scrolling social media, seeing promises like “fix this with one exercise” or “bulletproof your body with this one drill,” and feeling like they need to do more. That mindset is rarely helpful.

Before we go further, let’s briefly revisit what training actually is.

At its core, training is intentionally stressing the body at a specific dose within its window of tolerance, then allowing time to recover. During that recovery, the body adapts so that it can handle that stress a little better the next time. Then we apply slightly more stress, within this newly expanded window, and capacity grows. That’s how progress happens.

What the Threat Bucket Represents

Imagine you have a bucket. The size of that bucket represents your total capacity for stress. That capacity isn’t just workouts and training volume. It includes your nervous system, physiology, emotions, relationships, and environment.

Examples of what might go into your threat bucket:

- A history of a right ankle sprain

- A tight left posterior pelvic floor

- Chronic mouth breathing that disrupts sleep

- A baby who isn’t sleeping

- Conflict in a relationship

- Increasing run volume

- Watching the news or doom scrolling social media

Suddenly, the bucket is full. When it overflows, symptoms appear—pain, burnout, poor recovery, or injury. For many women I work with, pelvic floor symptoms are tightly linked to stress (If this peaks your interest, stay tuned for pelvic floor support related announcements soon). When the bucket overfills, the pelvic floor often responds. If we blame that overflow solely on running mechanics or training volume, we miss the full picture.

Staying Within the Window of Tolerance

The goal isn’t to eliminate stress. Stress is inevitable. I love the following quote from Jessica Patching-Bunch.

The goal is to keep the stress within your window of tolerance so that the body has the opportunity to effectively respond to that stress. There are two main strategies:

- Expand the size of the bucket.

This means improving nervous system resilience, your ability to experience stress without flipping into overload. It’s not about avoiding stress; it’s about responding to it differently. Training the nervous system, alongside intentional and progressive physical training, expands your window of tolerance. - Remove items from the bucket.

Some stressors can be addressed directly. This is where you look at what is in your locus of control. Some stressors are inevitable. Some are removable. Pick one at a time and address it.

Practical Examples of Removing Threats

Take a previous right ankle sprain. Even if you don’t consciously notice it, your body perceives it with every step. That perception alters how you move. Addressing ankle mobility, foot pronation, and how that foot loads and integrates with the rest of the body can reduce that threat.

Consider a tight posterior pelvic floor on the left side. That tension can limit how well you load into mid-stance on that side with every stride. Working on length through the posterior pelvic floor, improving glute length, and learning to load that side more efficiently can remove that stressor from the bucket.

Some stressors, like a baby who isn’t sleeping, aren’t fully controllable. Others are modifiable. Chronic mouth breathing that disrupts sleep might be improved with strategies like nasal breathing support, Breathe Right strips, or mouth tape.

It’s rarely one single thing. And realistically, you can only work on one thing at a time. Sitting down and identifying what’s filling your threat bucket and which items you have the tools and capacity to address is often a powerful first step.

When a New Threat Enters the Bucket

Pelvic floor issues are a clear example of how multifactorial stress works.

I worked with a postpartum client who had a prolapse and significant pelvic floor tension. Through movement work (improving posterior pelvic floor length and loading) her running and symptoms improved significantly.

Then she got a severe GI bug and was vomiting for more than 24 hours. After that, all her pelvic floor symptoms returned. Nothing we had done before was suddenly “wrong” or ineffective. A new, major stressor had entered the threat bucket. The GI illness increased pelvic floor guarding and tension, and the system tipped back into overload.

The fix: I had her lie on her back and hum. Inhaling through her nose, exhaling with a long, slow hum, for five minutes. She rolled her eyes at first. When she sat up, she said it was the first time her pelvic floor had relaxed in weeks.

This is another reminder: pain and symptoms are multifactorial. Biomechanics matter, and the work we did mattered. But when a new threat enters the bucket, symptoms can reappear. This is not because previous work was useless, but because the system is responding to a changed load.

Sometimes the new stressor is training-related. You may have pushed volume or intensity just a little beyond what your body was ready to handle, and the bucket overflowed. That’s not a failure. Everyone has a finite capacity for stress, and the entire purpose of training is to add stress on purpose. Overflow is part of the learning process.

The key is understanding your body, knowing how much stress your body can handle, recognizing your personal window of tolerance, and appreciating that everyone responds to stress differently. Two runners can follow the same plan and have completely different outcomes because their buckets are filled by different things.

Working Strategically, One Piece at a Time

The threat bucket analogy makes it clear that it’s rarely just one factor. But it also gives you a way forward that isn’t overwhelming. Instead of trying to fix everything at once, you can ask a simpler, more useful question: What is the biggest contributor to my threat bucket right now that I actually have control over?

From there, you address one thing at a time.

Sometimes that means reducing run volume or intensity. Sometimes it means spending five minutes on the floor humming and letting your nervous system settle. Other times, it really is biomechanical and adding targeted physical therapy style work into your training to address inefficiencies, improve loading, and remove those biomechanical threats can be helpful.

You do not have to do everything at once. Stressors will always exist. The goal is not to empty the bucket completely, but to understand what’s in it, what you can influence, and how your training fits into the larger context of your life as a whole human.

Looking Ahead

If this framework resonates with you, especially if pelvic floor symptoms are part of your running story, keep an eye out. I’ll be hosting a webinar in March where we’ll go deeper into these concepts and how they apply specifically to pelvic floor health and running. Once the official date is set, I’ll be sharing all the details.

In Conclusion

If you’ve been wondering, why am I suddenly struggling to run? the answer may not lie in your splits, your shoes, or your training plan alone. More often, it’s a reflection of your total stress load and whether it has exceeded your current capacity. Progress doesn’t require eliminating stress altogether, but understanding what’s filling your bucket and addressing one controllable factor at a time. When you zoom out and see the whole picture, you can move forward with clarity instead of panic—and build resilience that supports both your running and your life.

Next on Your Reading List

How to be a healthy runner when it comes to stress outside of training

Breaking Down the Link: Can Stress Cause Hip Pain? Unraveling the Intriguing Connection.

Your Postpartum Return to Running Plan: Building Strength, Coordination, and Confidence

Don't miss a thing!

Join my newsletter, be the first to know about what's coming up, and get even more great content!